I already wrote about the concept of outlier in Human Ancestry, so I am not going to repeat myself. This is just an update of “outliers” in recent studies, and their potential origins (here I will repeat some of the examples):

Early Khvalynsk: the three samples from the Samara region have quite different positions in PCA, from nearest to EHG (of Y-DNA haplogroup R1a) to nearest to ANE ancestry (of Y-DNA haplogroup Q). This could represent the initial consequences of the second wave of ANE ancestry – as found later in Yamna samples from a neighbouring region -, possibly brought then by Eurasian migrants related to haplogroup Q.

With only 3 samples, this is obviously just a tentative explanation of the finds. The samples can only be reasonably said to show an unstable time for the region in terms of admixture (i.e. probably migration), judging by the data on PCA.

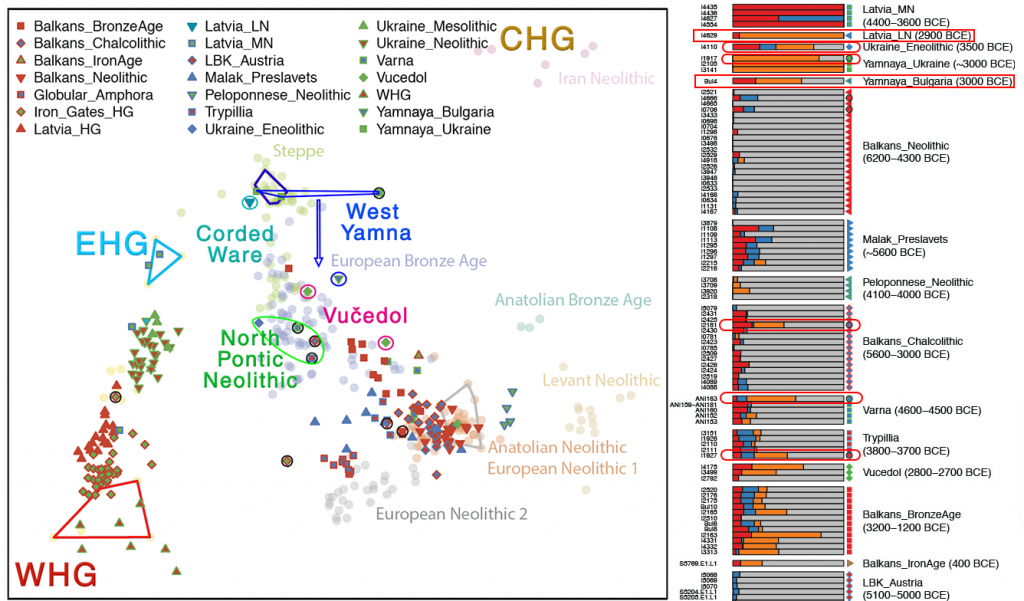

Ukraine Eneolithic samples offer a curious example of how the concept of outlier can change radically: from the third version (May 30th) of the preprint paper of Mathieson et al. (2017), when the Ukraine Eneolithic sample with steppe ancestry (and clustering with central European samples) was the ‘outlier’, to the fourth version (September 19th), when two samples with steppe ancestry clustering close to Corded Ware samples were now the ‘normal’ ones (i.e. those representing Ukraine Eneolithic population), and the outlier was the one clustering closely with Ukraine Mesolithic samples…

This is one of the funny consequences of the wrong interpretation of the ‘yamnaya component’, that made geneticists believe at first that, out of two samples (!), the ‘outlier’ was the one with ‘yamnaya’ ancestry, because this component would have been brought by an eastern immigrant from early Khvalynsk…

This example offers yet another reason why precise anthropological context is necessary to offer the right interpretation of results. Within the Indo-European demic diffusion model – based mainly on Archaeology and Linguistics – , the sample with steppe ancestry was the most logical find in the region for a potential origin of the Corded Ware culture, and it was interpreted as such, well before the publication of the fourth version of Mathieson et al. (2017).

West Yamna (to insist on the same question, the ‘yamnaya’ component): we have only four western Yamna samples, two of them showing Anatolian Neolithic ancestry (one of them, from Ukraine, with a strong ‘southern’ drift). On the other hand, Corded Ware migrants do not show this. So we could infer that their migrations were not coetaneous: whereas peoples of Corded Ware culture expanded ca. 3300 BC to the north – in the natural corridor to the Baltic that has been proposed for this culture in Archaeology for decades (and that is well represented by Ukraine Eneolithic samples) -, peoples of Yamna culture expanded to the west, replacing the Ukraine Eneolithic population (i.e. probably those of ‘Proto-Corded Ware culture’), and eventually mixing with Balkan populations of Anatolian Neolithic ancestry.

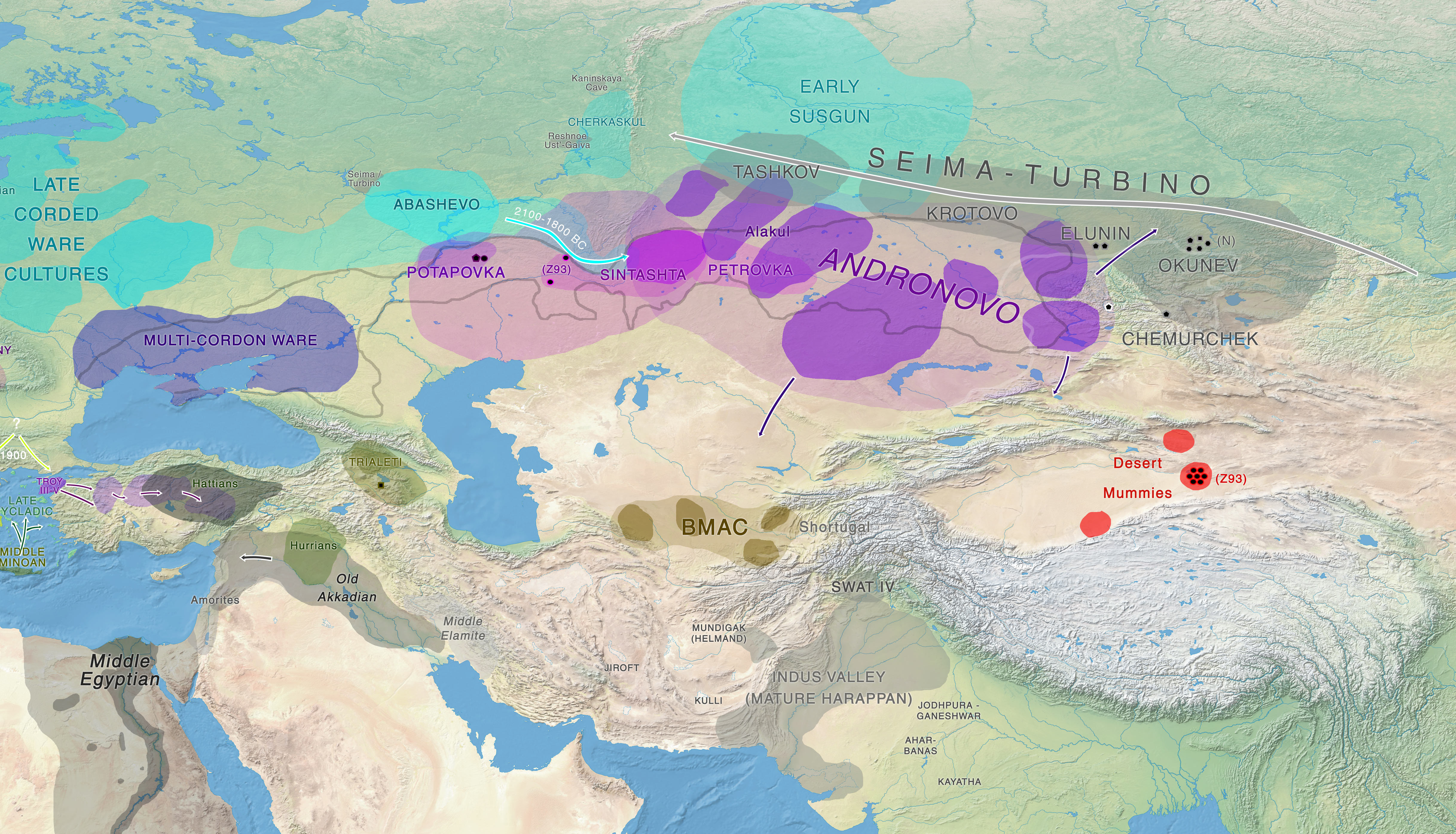

Potapovka, Andronovo, and Srubna: while Potapovka clusters closely to the steppe, and Andronovo (like Sintashta) clusters closely to Corded Ware (i.e. Ukraine Neolithic / Central-East European), both have certain ‘outliers’ in PCA: the former has one individual clustering closely to Corded Ware, and the latter to the steppe. Both ‘outliers’ fit well with the interpretation of the recent mixture of Corded Ware peoples with steppe populations, and they offer a different image for the evolution of populations of Potapovka and Sintashta-Petrovka, potentially influencing their language. The position of Srubna samples, nearer to Sintashta and Andronovo (but occupying the same territory as the previous Potapovka) offers the image of a late westward conquest from Corded Ware-related populations.

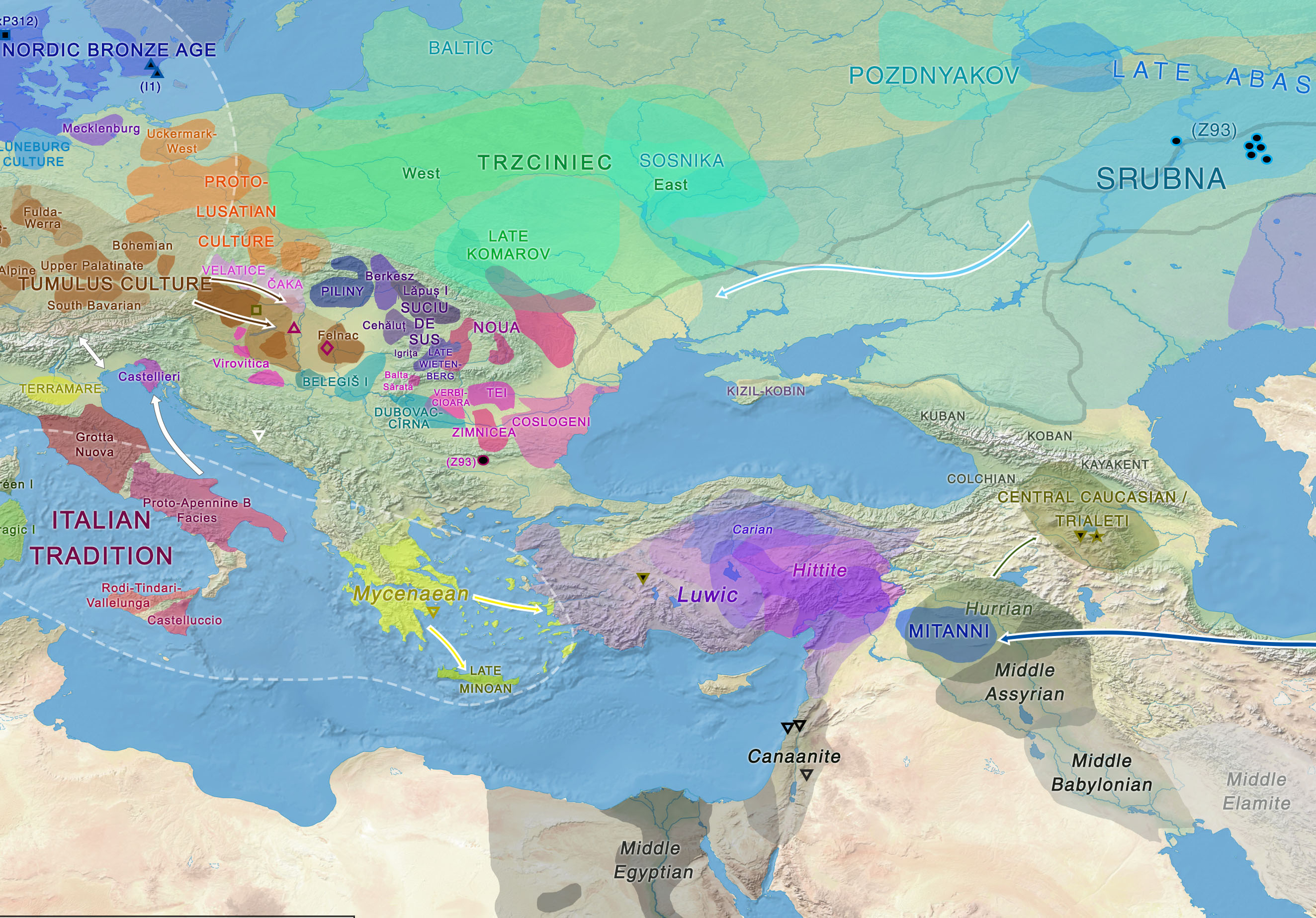

Iron Age Bulgaria: a sample of haplogroup R1a-z93, with more ‘yamnaya’ ancestry than any other previous sample from the Balkans. For some, it might mean continuity from an older time. However – as with the Corded Ware outlier from Esperstedt before it – it is more likely a recent migrant from the steppe. The most likely origin of this individual is therefore people from the steppe, i.e. either the Srubna culture or a related group. Its relatively close cluster in PCA to certain recent Slavic populations can be interpreted in light of the multiple back and forth migrations in the region: of steppe populations to the west (Srubna, Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians,…), and of Slavic-speaking populations:

- First as part of the Late Indo-European community to the west with Yamna / Bell Beakers, mixing early with Late Corded Ware groups either in Únětice or Mierzanowice/Nitra cultures;

- As an evolving Balto-Slavic-speaking community, probably within the Lusatian and descendant cultures, migrating gradually to the east, from the Bronze Age to Antiquity;

- And then rapidly expanding as a Proto-Slavic-speaking community from the steppe to the west.

Well-defined outliers are, therefore, essential to understand a recent history of admixture. On the other hand, the very concept of “outlier” can be a dangerous tool – when the lack of enough samples makes their classification as as such unjustified -, leading to the wrong interpretations.

Related:

- Indo-European demic diffusion model, 3rd edition (revised October 2017)

- The concept of “outlier” in studies of Human Ancestry, and the Corded Ware outlier from Esperstedt

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”

- Correlation does not mean causation: the damage of the ‘Yamnaya ancestral component’, and the ‘Future America’ hypothesis

- Something is very wrong with models based on the so-called ‘steppe admixture’ – and archaeologists are catching up