New preprint Late Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers in the Central Mediterranean: new archaeological and genetic data from the Late Epigravettian burial Oriente C (Favignana, Sicily), by Catalano et al. bioRxiv (2019).

Interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

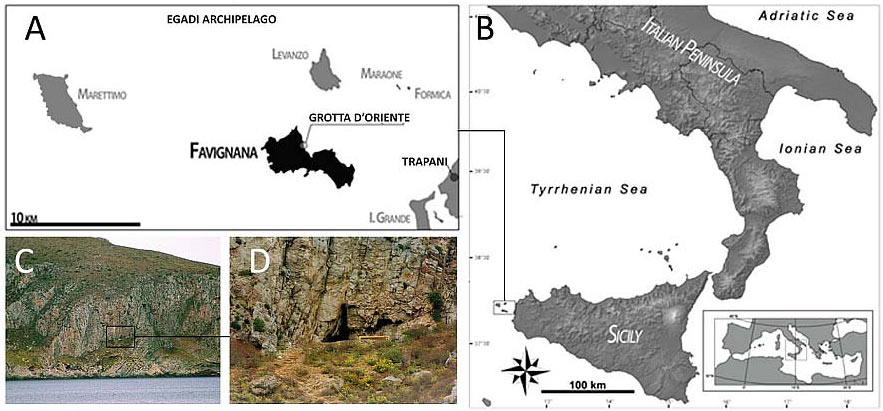

Grotta d’Oriente is a small coastal cave located on the island of Favignana, the largest (~20 km2) of a group of small islands forming the Egadi Archipelago, ~5 km from the NW coast of Sicily.

The Oriente C funeral pit opens in the lower portion of layer 7, specifically sublayer 7D. Two radiocarbon dates on charcoal from the sublayers 7D (12149±65 uncal. BP) and 7E, 12132±80 uncal. BP are consistent with the associated Late Epigravettian lithic assemblages (Lo Vetro and Martini, 2012; Martini et al., 2012b) and refer the burial to a period between about 14200-13800 cal. BP, when Favignana was connected to the main island (Agnesi et al., 1993; Antonioli et al., 2002; Mannino et al. 2014).

The anatomical features of Oriente C are close to those of Late Upper Palaeolithic populations of the Mediterranean and show strong affinity with other Palaeolithic individuals of Sicily. As suggested by Henke (1989) and Fabbri (1995) the hunter-gatherer populations were morphologically rather uniform.

Genetic analysis

We confirmed the originally reported mitochondrial haplogroup assignment of U2’3’4’7’8’9. This haplogroup is present in both pre- and post-LGM populations, but is rare by the Mesolithic, when U5 dominates (Posth et al.2016).

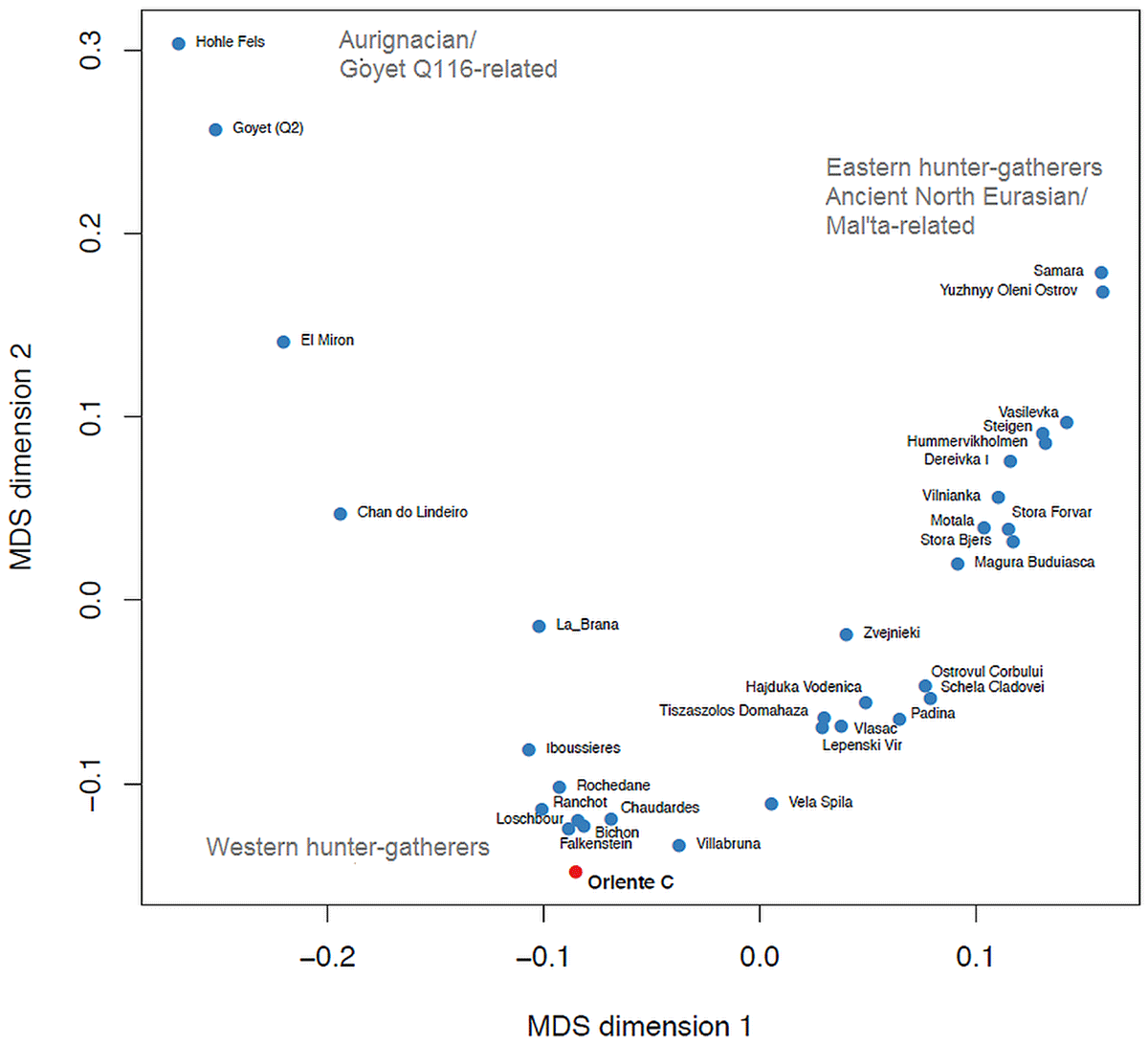

Lipson et al. (2018) (their supplementary Figure S5.1) and Villalba-Mouco et al. (2019) (their Figure 2A) showed that European Late Palaeolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers fall along two main axes of genetic variation. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) of f3-statistics shows that these axes form a “V” shape (Fig. 3). (…)

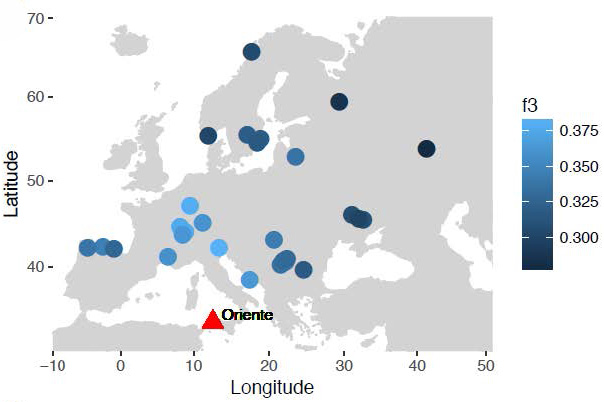

Focusing further on Oriente C, we find that it shares most drift with individuals from Northern Italy, Switzerland and Luxembourg, and less with individuals from Iberia, Scandinavia, and East and Southeast Europe (Fig. 4A-B). Shared drift decreases significantly with distance (Fig. 4C) and with time (Fig. 4D) although in a linear model of drift with distance and time as a covariate, only distance (p=1.3×10-6) and not time (p=0.11) is significant. Consistent with the overall E-W cline in hunter-gatherer ancestry, genetic distance to Oriente C increases more rapidly with longitude than latitude, although this may also be affected by geographic features. For example, Oriente C shares significantly more drift with the 8,000 year-old 1,400 km distant individual from Loschbour in Luxembourg (Lazaridis et al.,2014), than with the 9,000 year old individual from Vela Spila in Croatia (Mathieson et al.,2018) only 700 km away as shown by the D-statistic (Patterson et al.,2012) D (Mbuti, Oriente C, Vela Spila, Villabruna); Z=3.42. Oriente C’s heterozygosity was slightly lower than Villabruna (14% lower at 1240k transversion sites), but this difference is not significant (bootstrap P=0.12).

Discussion and Conclusion

The robust record of radiocarbon dates proves that they reached Sicily not before 15-14 ka cal. BP, several millennia after the LGM peak. In our opinion, in fact, the hypothesis about an early colonization of Sicily by Aurignacians (Laplace, 1964; Chilardi et al., 1996) must be rejected, on the basis of a recent reinterpretation of the techno-typological features of the lithic industries from Riparo di Fontana Nuova (Martini et al., 2007; Lo Vetro and Martini, 2012; on this topic see also Di Maida et al., 2019).

These analyses have implications for understanding the origin and diffusion of the hunter-gatherers that inhabited Europe during the Late Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic. Our findings indicate that Oriente C shows a strong genetic relationship with Western European Late Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, suggesting that the “Western hunter-gatherers” was a homogeneous population widely distributed in the Central Mediterranean, presumably as a consequence of continuous gene flow among different groups, or a range expansion following the LGM.

The South Italian corridor

Once again, a hypothesis based on phylogeography – apart from scarce archaeological and palaeolinguistic data (“Semitic”-like topo-hydronymy and substrates in Europe) – seems to be confirmed step by step. Since the finding of the Villabruna individual of hg. R1b-L754 (likely R1b-V88, like south-eastern European lineages expanded with WHG ancestry), it was quite likely to find out that southern Europe was the origin of the expansion of R1b-V88 into Africa.

The most likely explanation for the presence of “archaic” R1b-V88 subclades among modern Sardinians was, therefore, that they represented a remnant from a Late Upper Palaeolithic/Early Mesolithic population that had not been replaced in subsequent migrations, and thus that the migration of these lineages into Northern Africa and the Green Sahara happened during a period when Italy was connected by a shallower Mediterranean (and more land connections) to Northern Africa.

Nevertheless, the arguments for a quite recent expansion of R1b-V88 through the Mediterranean and into Africa keep being repeated, probably based on ancestry from the few ancient (and many modern) populations that have been investigated to date, a simplistic approach prone to important errors that overarch whole migration models.

For example, in the recent paper by Marcus et al. (2019) the presence of these lineages among ancient Sardinians (from the late 4th millennium BC on) is interpreted as an expansion of R1b-V88 with the Cardial Neolithic based on their ancestry, disregarding the millennia-long gap between these samples and the presence of this haplogroup in Palaeolithic/Mesolithic Northern Iberia and Northern Italy, and the comparatively much earlier splits in the phylogenetic tree and dispersal among African populations.

Afroasiatic and Nostratic

I was asked recently if I really believed that we could reconstruct Proto-Nostratic and connect it with any ancestral population. My answer is simple: until the Chalcolithic – when the whole picture of Indo-Europeans, Uralians, Egyptians or Semites becomes quite clear – we have just very few (linguistic, archaeological, genetic) dots which we would like to connect, and we do so the best we can. The earlier the population and proto-language, the more difficult this task becomes.

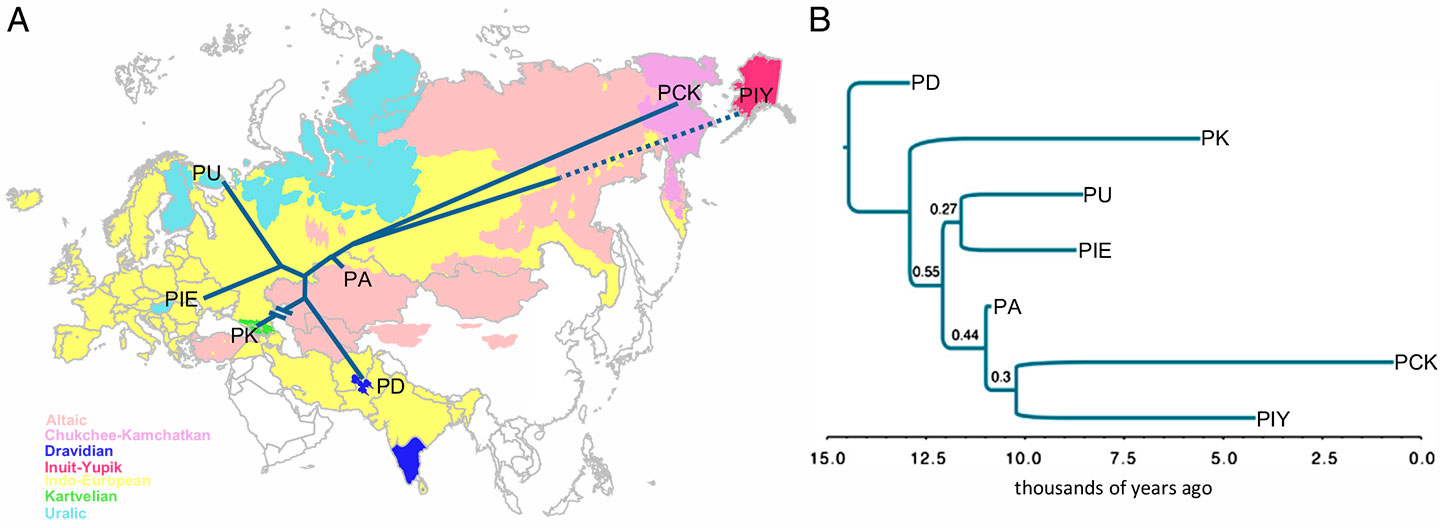

NOTE. 1) I tentatively connected hg. R with Nostratic in a previous text – when it appeared that R1a expanded from around Lake Baikal, hence Eurasiatic; R1b from the south with AME-WHG ancestry, hence Afroasiatic; and R2 with Dravidian.

2) After that, I though it was more likely to be connected to AME ancestry and the Middle East, because of the apparent expansion of WHG from south-eastern Europe, and the potential association of Afroasiatic and (Elamo-?)Dravidian to Middle Eastern populations.

3) However, after finding more and more R1b samples expanding through northern Eurasia, spreading through the (then wider) steppe regions; and R1a essentially surviving among other groups in eastern Europe for thousands of years without being associated to significant migrations (like, say, hg. C after the Palaeolithic), it didn’t seem like this division was accurate, hence my most recent version.

But, in essence, it’s all about connecting the dots, and we have very few of them…

In linguistics, I trust traditional linguists who tend to trust other more experimental linguists (like Hyllested or Kortlandt) who consider that – in their experience – an Indo-Uralic and a Eurasiatic phylum can be reconstructed. Similarly, linguists like Kortlandt are apparently (partially) supportive of attempts like that of Allan Bomhard with Nostratic – although almost everyone is critic of the Muscovite school‘s attachment to the Brugmannian reconstruction, stuck in pre-laryngeal Proto-Indo-Anatolian and similar archaisms.

I mostly use Nostratic as a way to give a simplistic ethnolinguistic label to the genetically related prehistoric peoples whose languages we will probably never know. I think it’s becoming clear that the strongest connection right now with the expansion of potential Eurasiatic dialects is offered by ANE-related populations (hence Y-chromosome bottlenecks under hg. R, Q, probably also N), however complicated the reconstruction of that hypothetic community (and its dialectalization) may be.

Therefore, the multiple expansions of lineages more or less closely associated to ANE-related peoples – like R1b-V88 in the case of Afrasian, or R2 in the case of Dravidians – are the easiest to link to the traditionally described Nostratic dialects and their highly hypothetic relationship.

What should be clear to anyone is that the attempt of many modern Afroasiatic speakers to connect their language to their own (or their own community’s main) haplogroups, frequently E and/or J, is flawed for many reasons; it was simplistic in the 2000s, but it is absurd after the advent of ancient DNA investigation and more recent investigation on SNP mutation rates. R1b-V88 should have been on the table of discussions about the expansion of Afroasiatic communities through the Green Sahara long ago, whether one supports a Nostratic phylum or not.

The fact that the role of R1b bottlenecks and expansions in the spread of Afroasiatic is usually not even discussed despite their likely connection with the most recent population expansions through the Green Sahara fitting a reasonable time frame for Proto-Afroasiatic reconstruction, a reasonable geographical homeland, and a compatible dialectal division – unlike many other proposed (E or J) subclades – reveals (once again) a lot about the reasons behind amateur interest in genetics.

Just like seeing the fixation in (and immobility of) recent writings about the role of I1, I2, or (more recently) R1a in the Proto-Indo-European expansion, R1b with Vasconic, or N1c with Proto-Uralic.

NOTE. That evident interest notwithstanding, it is undeniable that we have a much better understanding of the expansions of R1b subclades than other haplogroups, probably due in great part to the easier recovery of ancient DNA from Eurasia (and Europe in particular), for many different – sociopolitical, geographical, technological – reasons. It is quite possible that a more thorough temporal transect of ancient DNA from the Middle East and Africa might radically change our understanding of population movements, especially those related to the Afroasiatic expansion. I am referring in this post to interpretations based on the data we currently have, despite that potential R1b-based bias.

Related

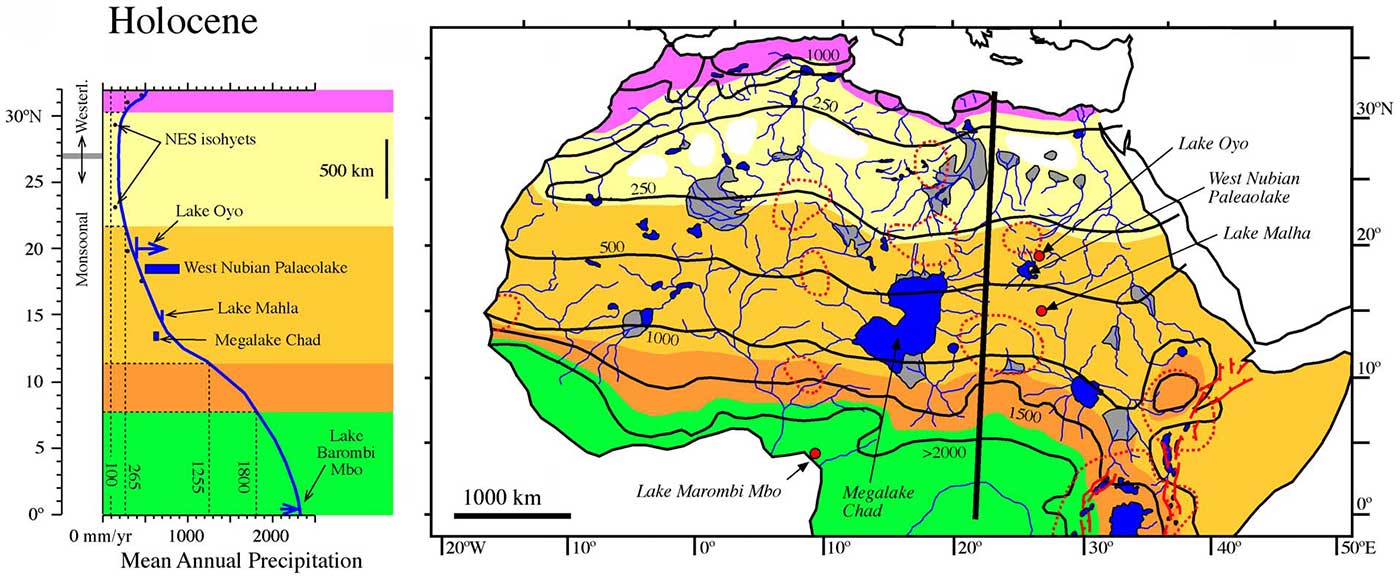

- Sahara’s rather pale-green and discontinuous Sahelo-Sudanian steppe corridor, and the R1b – Afroasiatic connection

- R1b-V88 migration through Southern Italy into Green Sahara corridor, and the Afroasiatic connection

- Fulani from Cameroon show ancestry similar to Afroasiatic speakers from East Africa

- Genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia; Botai shows R1b-M73

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- Ancient genomes from North Africa evidence Neolithic migrations to the Maghreb

- Tales of Human Migration, Admixture, and Selection in Africa

- Pleistocene North African genomes link Near Eastern and sub-Saharan African human populations

- Genetic ancestry of Hadza and Sandawe peoples reveals ancient population structure in Africa

- Potential Afroasiatic Urheimat near Lake Megachad

- The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia

- Genetic landscapes showing human genetic diversity aligning with geography

- Human ancestry solves language questions? New admixture citebait