The recent study of Estonian Late Bronze Age/Iron Age samples has shown, as expected, large genetic continuity of Corded Ware populations in the East Baltic area, where West Uralic is known to have been spoken since at least the Early Bronze Age.

The most interesting news was that, unexpectedly for many, the impact of “Siberian ancestry” (whatever that actually means) was small, slow, and gradual, with slight increases found up to the Middle Ages, compatible with multiple contact events in north-eastern Europe. Haplogroup N became prevalent among Finnic populations only through late bottlenecks, as research of modern populations have long suggested, and as ancient DNA research hinted since at least 2015.

I risked to correlate the arrival of chiefs from the south-west with the infiltration of N1c-VL29 subclades during the transition to the Iron Age, coupled with that minimal “Siberian” ancestry (see e.g. here and here). Now we know that the penetration of this non-CW ancestry started, as predicted, in the Iron Age; that it was highly variable in the few samples where it appeared, with ca. 1-4%, while most Iron Age individuals show 0%; and that it was not especially linked to individuals of N1c-Vl29 lineages.

It is also basically confirmed, based on the (ancient and Modern Swedish) N1c-L550 subclades found among Iron Age Estonians, that N1c-VL29 lineages and the so-called “Siberian” ancestry will be found simultaneously around the Baltic coastal areas, and that different lineages must have suffered later founder effects among Finns, which suggests that these alliances through exogamy brought exactly as much language change in Sweden, Lithuania, or Poland, as they did in the East Baltic region…

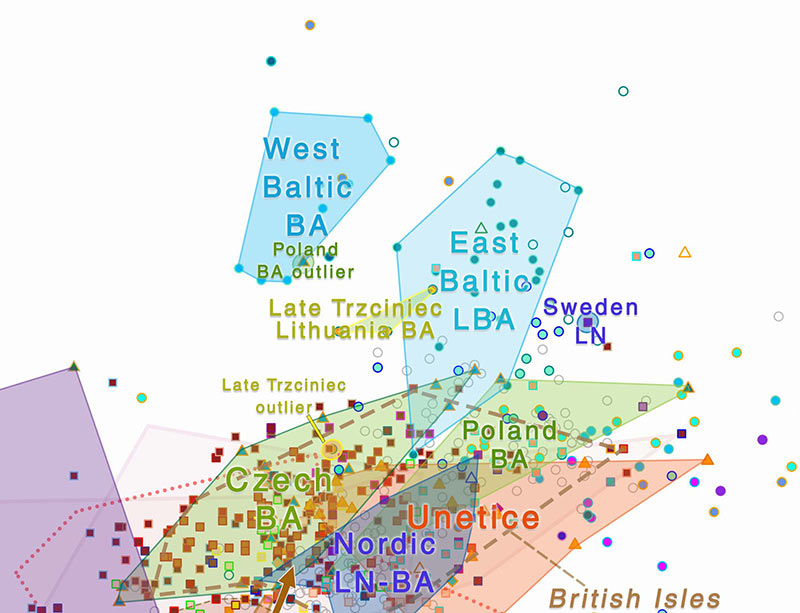

On the other hand, the paper has also shown a potential movement of Corded Ware-derived peoples, if the change from LBA to IA samples is meaningful; in fact, even more Corded Ware-like than Baltic and Estonian BA populations. The exact origin of that movement is difficult to pinpoint, and it may not be related to the arrival of Akozino warrior-traders from the south-east, since theirs seems to be a minor impact proper of elites in a chiefdom system around the Baltic.

Also suggesting a potential movement is the ‘southern’ shift observed in the West and East Baltic areas, likely showing the arrival of Proto-East Baltic speakers (such as the Trzciniec outlier), as we have already discussed in this blog. The unexpected increase in Corded Ware-like ancestry in the Eastern Baltic, coupled with the expected large continuity of hg. R1a-Z283 in the homeland of Balto-Finnic expansions, gives even more support to the known complex system of exogamy along the Baltic coasts, and offers another potential reason for the rise of Baltic-speaking territories in the West Baltic: elite domination.

It is nevertheless important to understand that, even among the most “genetic continuous” regions like Estonia, not a single population in Europe is heir of some ancestral, immutable people. Not in terms of haplogroups, and not in terms of admixture. Balto-Finnic speakers, however continuous they might seem (e.g. in Southern Estonians) aren’t an exception.

After all, this blog was (re)born to fight the currently prevalent sheer stupidity surrounding the simplistic “R1a/steppe ancestry=Indo-European” association, so I wouldn’t like to see it replaced with some other stupid continuity or purity ideas within 10 to 20 years…

Late Uralic stems from East Corded Ware groups

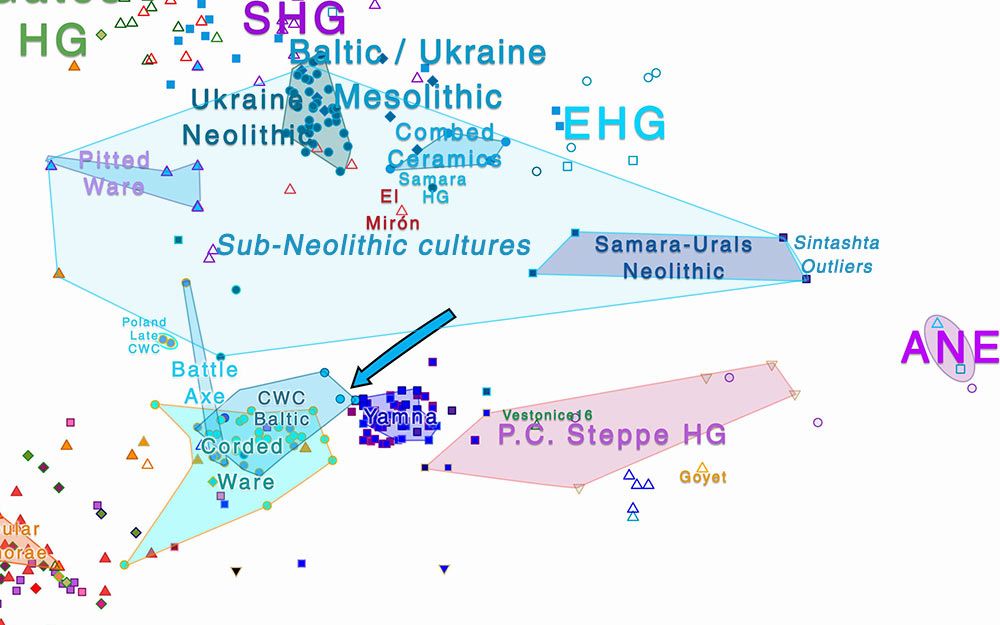

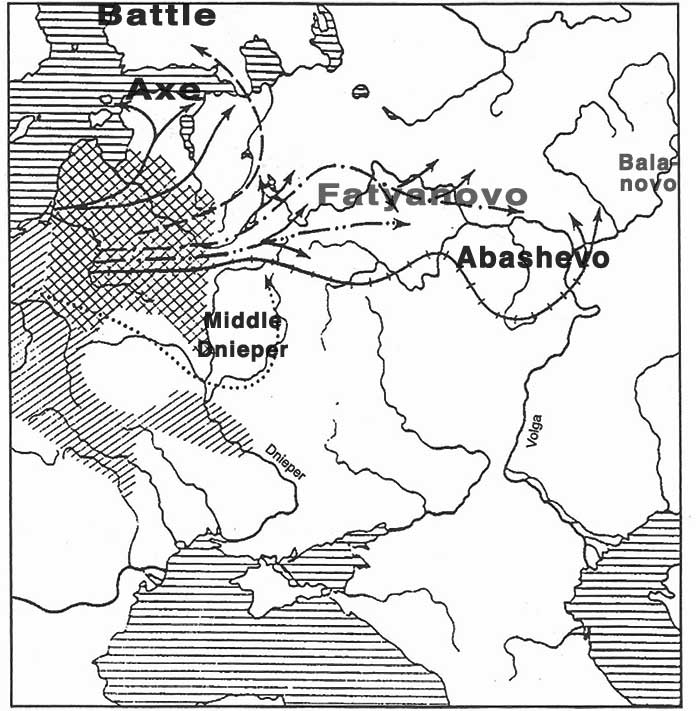

With the currently available tools – linguistics, archaeology, and now genetics -, I don’t think there is any argument to date to question the direct connection of the Late Proto-Uralic expansion with all Eastern Corded Ware groups (i.e. Battle Axe, Fatyanovo-Balanovo, and Abashevo), and thus at least with the unifying A-horizon of Corded Ware and the bottlenecks under R1a-Z645.

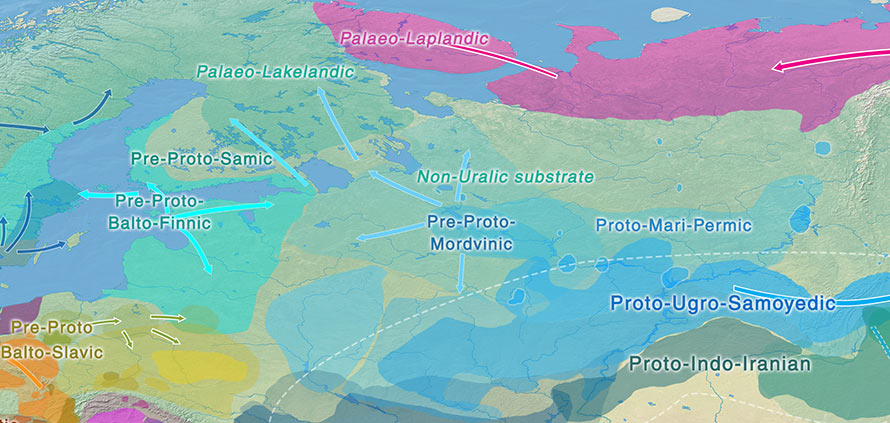

NOTE. The only out-group among Corded Ware cultures is the Single Grave culture. It appears to be an early Corded Ware offshoot, reflected in their non-unitary cultural traits (distinct from later unifying waves), in their varied patrilineal clans, and in the short-lasting cultural effect in northern Europe before their complete demise under pressure of expanding Yamna/Bell Beaker peoples from the Danube. The culture’s minimal (if any) effects on succeeding peoples might be seen mostly in the (mainly phonetic) Uralic substrate found in Balto-Slavic – although this may also stem from a more eastern influence, close to the Baltic – and in the contacts of Celtic with Uralic. The huge time depth between this early hypothetic Uralic layer in northern Europe and the emergence of peoples inhabiting these territories in recorded history have no doubt been erroneously interpreted as a lack of Uralic presence in the area.

1) That connection was evident in the Yamna – CWC differences in archaeology, and especially later, with at least Fatyanovo-Balanovo and Abashevo representing the obvious replacement of the Volosovo culture before further expansions of CWC-related groups west and east of the Urals.

The mythical millennia-long continuity of Volosovo hunter-gatherers, including centuries among Corded Ware peoples, as expected lately by the Copenhagen group (and anyone who doesn’t want to question the 1960s association of Indo-European with CWC) must be rejected today in population genomics, as the recent studies of ancient and modern populations show, and as ancient DNA from the region will confirm.

2) In linguistics, the survival of Volosovo as The Uralic-speaking culture was also hardly believable. From Kallio (2015):

While we can say at least something about Uralic substrates in Northeastern Europe, non-Uralic substrates cannot at all easily be identified, because of multiple language shifts, viz. first from non-Uralic to Uralic and then from Uralic to Russian. Yet the Soviet Uralicist Boris Serebrennikov (1956, 1959) argued that there are some non-Uralic substrate toponyms in the Volga-Oka region, but his idea was never taken seriously in the west (cf. Sauvageot 1958), and it pretty soon also sank into oblivion in Russia, even though it can still occasionally pop up there in non-onomastic circles (cf. Napolskikh 1995: 18–19). However, not all the hypotheses on non-Uralic substrates in Northeastern Europe should be rejected (see e.g. Helimski 2001b).

Helimski (2001) argues for a non-Uralic topo-hydronomy in Northern Russia, whose population may have kept their languages up to the Common Era despite the Corded Ware expansion, which is in line with the survival of some non-Indo-European languages everywhere in Europe after the expansion of Yamna and its offshoots:

It should be borne in mind that these [Uralic] hydronyms reached us mainly through Northern Russian and, accordingly, with a tendency to phonetic-morphological adaptation and unification (for river names it is “natural” to be, like the word ‘river’ itself, feminine and to end in -a). Taking into account this circumstance, it may turn out to be non-useless for etymological identification of at least some of the hydronyms on the Finno-Ugric basis.

On the other hand, I wouldn’t exclude the possibility that some parts of this large geographical area were never (completely) Finno-Ugric. The population that created the most important part of the hydronymy of the Russian North could be finally pushed aside or assimilated only at the end of the 1st – beginning of the 2nd millennium AD, during the Russian colonization, retaining the memory of the White-Eyed Chude in its own memory.

NOTE. For more on this non-IE substrate in (especially West) Uralic, see e.g. Zhivlov (2015),

The same non-Uralic substrate is most likely behind most of the shared traits by Mordvinic and Balto-Finnic (see below).

3) In genetics, I don’t think the picture could get any clearer. I don’t know what “Steppe ancestry = Indo-European” proponents expected from 2019, if they expected anything at all (I haven’t seen any coherent model, proposal, or prediction for a long time now), but I doubt the recent results are compatible with any of their implied expectations.

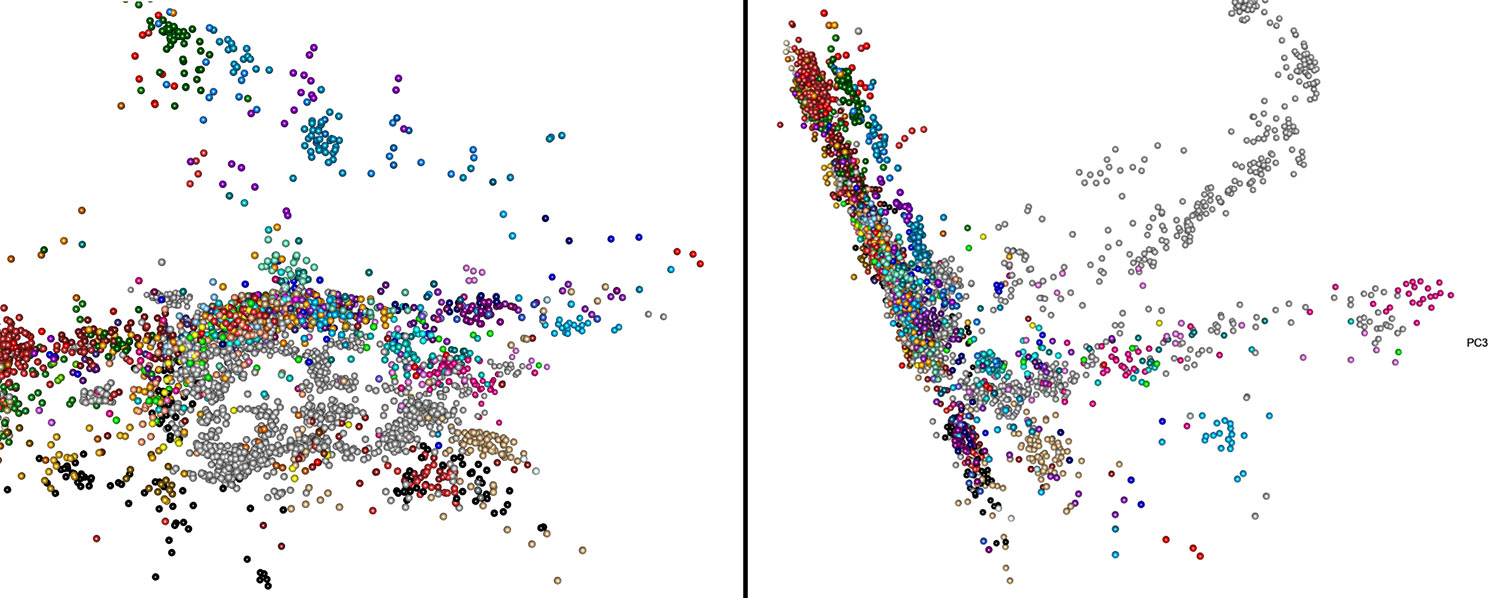

Notice, from the PCA above, how this Baltic Late Neolithic group shows actually a shift from Sredni Stog (see PCA with Sredni Stog) towards typical Khvalynsk-Urals-related ancestry, i.e. populations from eastern European forested regions, derived from hunter-gatherer pottery groups, as I have proposed for a very long time, since the first time a Baltic LN “outlier” appeared. It’s amazing how some amateurs can find 0.1% of any Siberian outlier’s ancestry among Uralians 4,000 years later, but fail to see the direct connection here. The esoteric uses of qpAdm, I guess…

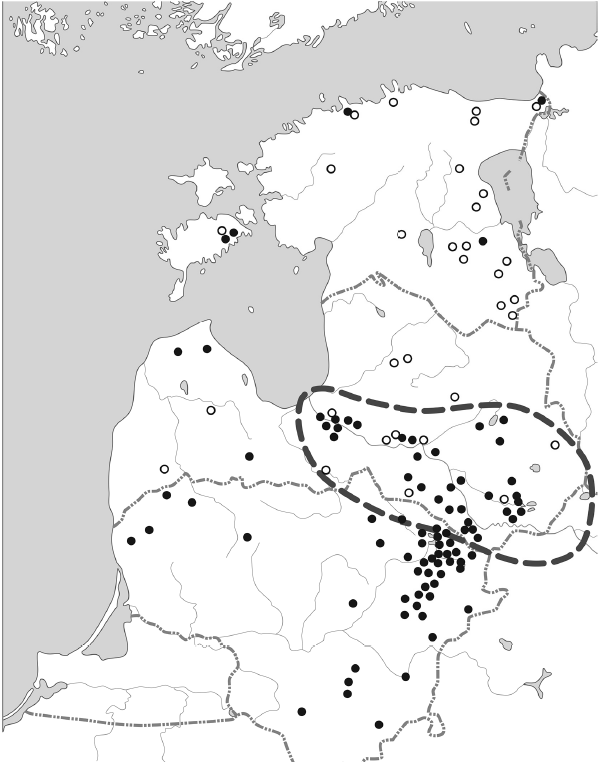

Especially noticeable is the extra WHG-like ancestry and corresponding shift, seen especially marked in late Polish CWC samples, but also in Baltic CWC and especially in one Sweden Battle Axe sample, all of them shifting apparently closer to Pitted Ware and SHG. While that may have been interpreted as an in situ admixture in Scandinavia before, the late Polish CWC samples show likely a resurgence of local populations, so we can assume that both shifts (to SHG- and EHG-like populations) of available CWC samples around the Baltic are clearly part of the WHG:EHG continuum that will be found in the eastern European sub-Neolithic cultures, from Narva to Volosovo.

This WHG-related ancestry is clearly predominant in groups with which Battle Axe peoples admixed, based on the shift towards Pitted Ware, which – I can only guess based on modern Volga Finns – is different from the shift we will see in Netted Ware, more towards the Khvalynsk-Urals cluster. This is in line with the expansion of Battle Axe eastward through coastal areas (West to East Baltic and Finland into Sweden), while Fatyanovo peoples probably emerged from a slightly different route, but also a northern one, if one is to follow archaological similarities and their chronology.

During the Iron Age, the only peoples that probably shifted strongly (based on modern populations) are West Baltic ones, getting closer to the available Late Trzciniec samples, and even closer to the Trzciniec outlier, i.e. away from the earlier Eastern Corded Ware cluster, and towards Central European groups like Czech EBA or Poland EBA, both of them clearly derived from Bell Beakers, but also admixed with (and thus shifted toward) CW-like populations.

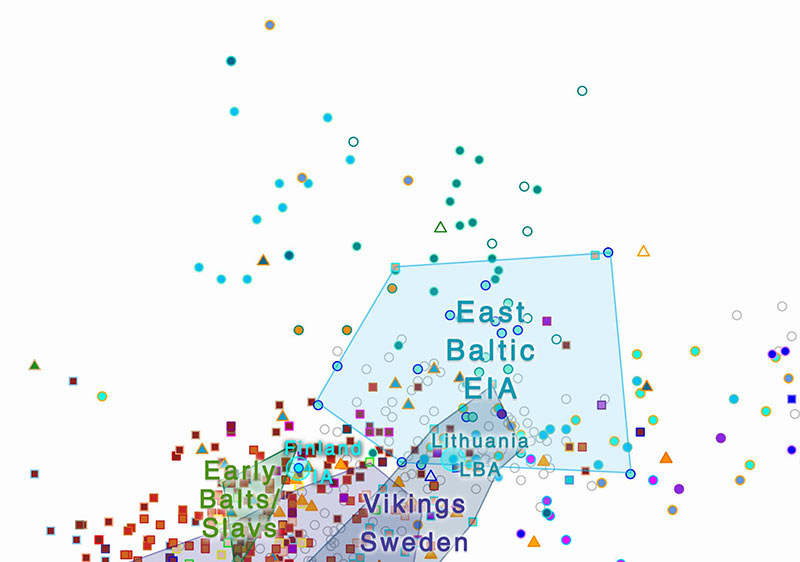

If one looks carefully at the previous PCA on Bronze Age populations, and the next one on Iron Age clusters, it is evident that adding the Swedish LN outlier to East Baltic BA (both strongly related to Battle Axe populations) essentially gives us the continuity of East Baltic BA into the Iron Age. This cluster is continued also in two outliers from Sigtuna, a Viking town close to the Gulf of Finland, known to be an important trading site, 1,500 years later. Not much of a change around the Gulf of Finland, then:

Based on the two simplistic Uralic clines one might see described (among the many that certainly existed, from Corded Ware to different Eurasian populations), and just like BOO was for some months fashionable as “Samic”, some may be tempted to say that certain Sintashta or Srubna outliers close to the Urals mark the True Uralic™ peoples. Because, of course they do. Ghost haplogroup N and stuff. And Corded Ware never ever Uralic. Because Gimbutas, and my IE R1a grandfather.

NOTE. Funny thing here: there might be Corded Ware, Iranian, Slavic, Germanic, etc… outliers or out-groups, and they might form the widest genetic clusters ever seen, but they are all of one language, because archaeology and linguistics; however, one “outlier” (also, put your own definition of “outlier” here, let’s say 1% of whatever, and strontium isotope potentially from 100 km away) ca. 600 BC in the Baltic who (surprise!) happens to show hg. N, and he signals the first incoming True Uralic™ speaker from wherever… It won’t be the first or the last time some people resort to “the complexity of Uralic-speaking peoples” in ancestry, just to look for “hg. N = Uralic” like crazy. You only need common sense to understand that this is not how this works. Amateur genomics can’t get more embarrassing than the current “let’s look for ‘Siberian ancestry’ in every individual of haplogroup N” trend. Or maybe it can, and it will, but I can’t see it yet.

If one were to insist on looking for ‘foreign’ contributions among Iron Age Estonians, though, I think one should also check out first archaeology, and then the PC3 (or, more graphically, a 3D plot), to understand what might be happening with the many Uralic clines derived from Corded Ware, before starting to play around with bioinformatic tools to discover a teeny tiny 1% admixture of the wrong population, and rushing to build far-fetched narratives. Apparently, one of the different clines formed roughly between southern (steppe – forest-steppe) and northern (tundra-taiga) populations in Uralians is also seen in some Iron Age Estonian individuals – especially in some late samples from Ingria…This is not my main interest, so I will leave this here for others to keep wasting their time chasing the white whale of the 0.5% of True Uralic™ ancestry in ancient Baltic samples of hg. N.

An exclusive Volga-Kama homeland for Disintegrating Uralic?

Since I don’t believe in macro-regions of largely continuous ethnolinguistic communities, as I have often said about Slavic (naively associated with prehistoric tribes of Eastern Europe) or Germanic (absurdly considered to be represented by Battle Axe), it is difficult for me to believe that Battle Axe-derived cultures remained of the same Finno-Samic dialects since the Corded Ware expansion…unless we live in Westeros, where everything happens “for thousands of years”.

I have to admit, then, that the now prevalent identification among Uralicists has become quite attractive:

- Fatyanovo-Balanovo as Finno-Permic:

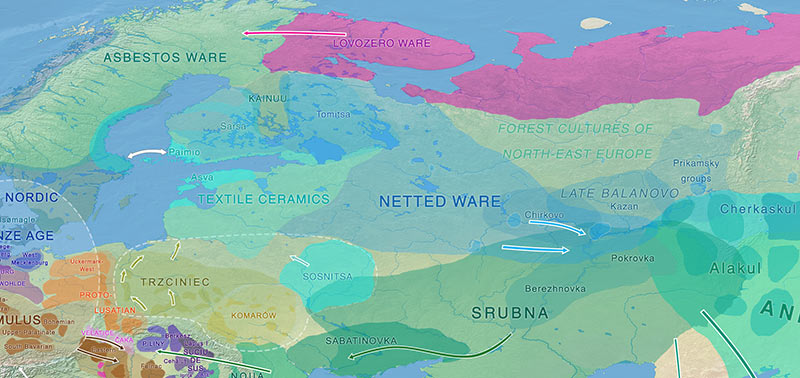

- Fatyanovo/Netted Ware with West Uralic (also called Finno-Mordvinic).

- Balanovo/Chirkovo-Kazan with Central Uralic (Mari-Permic).

- Abashevo, into the Andronovo-like Horizon through the Seima-Turbino phenomenon, with East Uralic (also Ugro-Samoyedic).

Exactly like the identification of Yamna Hungary – Bell Beaker transition as the North-West Indo-European homeland, it gives us simplicity and small and late ethnolinguistic communities, away from the traditionally overused big and early language territories.

This late homeland would be supported, among others, by:

- The presence of Indo-Iranian loanwords in Finno-Permic and Ugric (probably also in Samoyedic, either lost, or – much more likely – underresearched), compatible with the immediate contact between Abashevo – Sintashta-Potapovka-Filatovka and Fatyanovo-Balanovo.

- The supposed expansion of Netted Ware from Fatyanovo to the north-west, which may be explained as the split and expansion of Balto-Finnic and Samic ca. 1900 BC.

- A longer-lasting Finno-Permic (West+Central Uralic) community contrasting with the early separation of East Uralic.

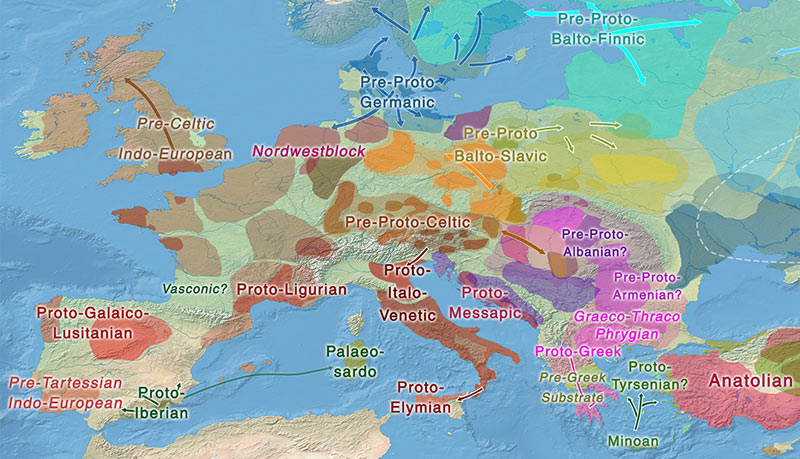

- The compatibility of this late expansion with the late expansion of Pre-Germanic from Denmark with the Dagger Period, and of Balto-Slavic with Trzciniec, which puts all three dialects reaching the Baltic Sea in the EBA.

NOTE. I meant to update the linguistic text to include the most recently favoured phylogenetic tree of Uralic languages after Häkkinen (2007, 2009, 2014), which has very quickly become the new normal among Uralicists, but I don’t think I will have enough time to review the necessary papers for that. I am rushing to publish a printed edition, so the text will wind up being a mixture of “traditional” (meaning, basically, pre-2010s) description of Uralic dialects but using modern divisions; say, “West Uralic” instead of “Finno-Samic”. By the way, I am still amazed that none of my reader-haters (or any online user discussing Uralic migrations, for that matter) have come up with the questions that the new division pose, and it supports my suspicion about the complete lack of interest in linguistics of most (a)DNA fans, except for the occasional use of old and free PDFs Googled to support new narratives invented expressly for some qpAdm results…

Problems with this Parpola-Carpelan’s (2012-2018) interpretation include:

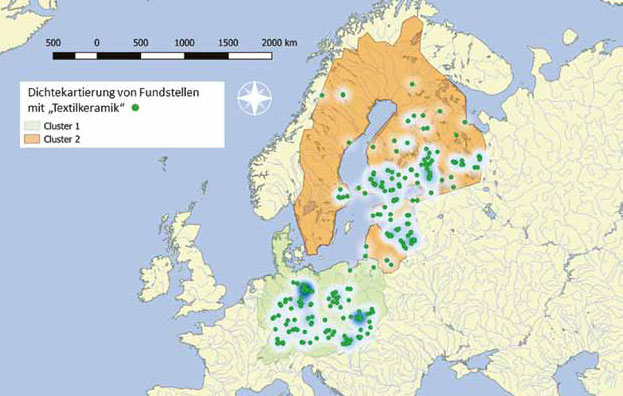

- The differentiation between Fennoscandian Textile Ceramics vs. Netted Ware, which is not warranted in archaeology. The assumption that Netted Ware expanded to the Baltic Sea (as Kallio does, following the traditional view) is thus weak, and it was probably a question of cultural contacts coupled with short-distance population movements/exchange in both directions (from the Baltic to the Volga and vice versa). In fact, the culture division relies on some fairly common and technically simple ornamentation patterns, widespread all over northern Europe, even before the Corded Ware expansion, and it is very difficult to separate certain neighboring Textile Ceramics from Netted Ware groups in southern Finland (i.e. Sarsa-Tomitsa groups).

- The strict and radical direction described for the Netted Ware by Carpelan, as an eastward and northward expansion, within a very short time frame (ca. 1900-1800 BC), based on few radiocarbon dates, which seems to me like a very risky assumption. We know how this kind of descriptions of direction of culture expansion based on radiocarbon dates has turned out in much more complex “packages”, like the Bell Beaker culture… In fact, the earliest dates for Textile Ware are from the East Baltic, earlier than those of Netted Ware.

- The assumption that Balto-Finnic traits shared with Mordvinic are a) late and b) meaningful for dialectalization of two closely related dialects, when it is clear that both dialects separated quite early. Phonologically Finnic is more conservative, morphologically less so, and the shared traits include a handful of non-Uralic substrate words which can’t be traced to a single common source, hence they were adopted when both languages had already separated… All in all, Finnic – Mordvinic correspondances are not even close to Italo-Celtic ones, which is clearly fully incompatible with a proposal of a Finnic separation from Mordvinic coinciding with the LBA-IA transition.

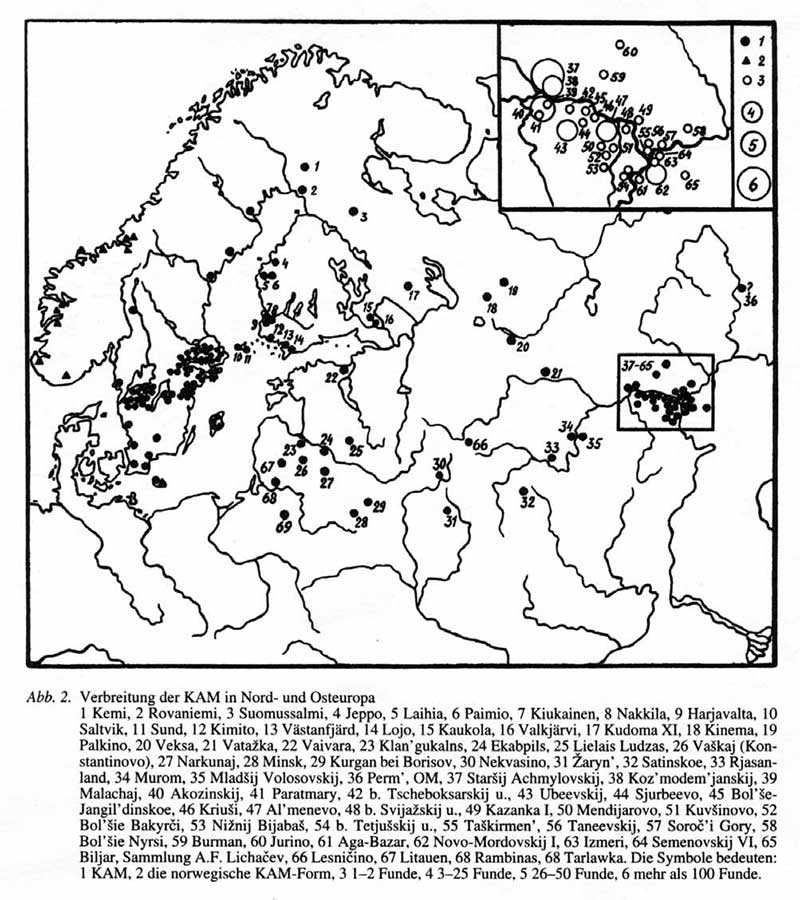

Especially problematic for Parpola’s model is the lack of genetic impact in Bronze Age or Iron Age Estonians, not reaching a significant level under any possible statistical threshold – which I am sure was quite disappointing for some of my readers -, but is in line with major archaeological continuity of groups the from region, only disturbed in cultural (and Y-chromosome) terms by the expansion of Akozino warrior-traders all over the Baltic Sea. Any proposed population movement will be very difficult to support in genetics, given the Corded Ware-derived populations that we will see in both regions, and the continued Baltic-Volga contacts since the Corded Ware expansion.

Problems with an interpretation of such a small impact in population genomics includes the similarly weak impacts and haplogroup infiltrations that can be seen among populations basically everywhere in Eurasia, during any given period, and much greater genetic impacts that are supposed to be (or that were certainly) followed by ethnolinguistic continuity.

The Battle Axe question

From Kallio (2015), about choosing a tentative homeland for Proto-Uralic:

(…) linguistically uniform Proto-Uralic would have been spoken in the Volga-Oka region until the mid-third millennium BC when the Proto-Uralic-speaking area would have expanded to the Volga-Kama region as well. By the end of the same millennium, this expansion would have led to the earliest dialectal splits within Uralic into Finno-Mordvin, Mari-Permic, and Ugro-Samoyed. The splitting up of these three soon followed during the early second millennium BC when the Uralic-speaking area finally stretched from the Baltic Sea in the west to the Altai mountains in the east. Indeed, no matter where Proto-Uralic was spoken, the branching into the nine well-attested subgroups (viz. Finnic, Saami, Mordvin, Mari, Permic, Hungarian, Mansi, Khanty, and Samoyed) must have taken less than a millennium, because their shared phonological and morphosyntactic isoglosses are rather limited (see Salminen 2002). The traditional view that all this branching would have taken several millennia violates everything linguistic typology teaches us about the rate of language change.

The basic problem of this identification of Fatyanovo-Balanovo as West-Central Uralic and Abashevo as East Uralic is the nature of the Battle Axe culture, including the Bronze Age East Baltic and Gulf of Finland area. Even if it is accepted that Fatyanovo-Balanovo represented all Western groups, Battle Axe must have represented West Uralic-like dialects.

The ethnolinguistic identification of Battle Axe depends ultimately on the nature of contacts of Fatyanovo/Netted Ware with Battle Axe/Textile Ceramics. If both groups were close and interacted profusely, as it seems, it doesn’t seem granted that we will be able to distinguish a close Para-West Uralic dialect of Scandinavia from the actual expanding Balto-Finnic and Samic dialects, if they were actually linked to the Netted Ware expansion. Also from Kallio (2015):

No doubt the most convincing substrate theory has recently been put forward by the Saami Uralicist Ante Aikio (2004), who has not only rehabilitated but also improved the old idea of a non-Uralic substrate in Saami. His study shows that there were still non-Uralic languages spoken in Northern Fennoscandia as recently as the first millennium AD. Most of all, they were not only genetically non-Uralic but also typologically non-Uralic-looking, bearing a closer resemblance to the so-called Palaeo-European substrates (for which see e.g. Schrijver 2001; Vennemann 2003).

In comparison, the case of Finnic is much more difficult. The fact that Proto-Uralic was not spoken in the East Baltic region means that this area must have originally been non-Uralic-speaking, but so far the evidence for a non-Uralic substrate in Finnic has consisted of appellatives and proper names with no etymology (cf. Ariste 1971; Saarikivi 2004a). Contrary to the proposed substrate words in Saami, those in Finnic show no structural non-Uralisms, as if they had indeed been borrowed from some genetically related or at least typologically similar languages, as I suggested above. Also none of them is more recent than the Middle Proto-Finnic stage, which makes them at least two millennia old. All this agrees with archaeological evidence discussed earlier that the Uralicization of the East Baltic region occurred during the Bronze Age (ca. 1900–500 BC).

The discussion of the paper continues with an unsuccessful attempt to find a hypothetical ancient Indo-European substrate that Kallio believes must be associated with the expansion of Corded Ware, in line with the traditional belief. For example, the often mentioned – almost folk etymology-like, unsurprisingly popular among amateurs – ‘Neva’ as derived from IE “young” is logically rejected…Unlike Parpola, Kallio’s view seems to be confident that Netted Ware (as Textile Ware) expanded into the East Baltic, on both sides of the Gulf of Finland, already during the Bronze Age.

As it has become apparent in population genomics, none of them was right, and Textile Ceramics will essentially show – like Netted Ware – a large genetic continuity of Corded Ware peoples in the whole north-eastern European forest zone – despite small regional population movements, obviously -, which necessarily implies that the whole Corded Ware culture – and not only Fatyanovo-Balanovo and Abashevo – were Uralic-speaking territories.

The similarities in terms of culture and Y-DNA bottlenecks between Battle Axe and Fatyanovo-Balanovo also imply that the linguistic differences between these groups were probably not many, and became strongly divided only after their territorial division. Continued contacts between Battle Axe- and Fatyanovo-derived groups can explain the proposed contacts (Finnic with Samic, Finnic with Mordvinic) after their linguistic-but-not-physical separation.

Battle Axe spoke “Para-Balto-Finnic”?

The Balto-Finnic-speaking nature of Battle Axe is thus supported by:

- The lack of non-Uralic substrates in Balto-Finnic territory (Kallio 2015).

- The early separation of Samic and Finnic from Mordvinic, and the virtual identity of Proto-West-Uralic and Proto-Uralic, which suggests that Proto-Uralic spread fast (Parpola 2012).

- The scarce non-Uralic topo-hydronymy in the East Baltic and around the Gulf of Finland (Saarikivi 2004), comparable to that on the Upper Volga region.

- The strong influence of a Balto-Finnic-like substrate on Pre-Germanic (or, in Kallio’s opinion, the same Scandinavian substrate influencing both Germanic and Balto-Finnic at the same time), and the continued influence of Balto-Finnic on Proto-Baltic and Proto-Slavic.

- The continued influence of Corded Ware-derived groups in central-east Sweden in Finland and the East Baltic in terms of agricultural innovations appearing in the LBA, compatible with Schrijver’s proposal of intermediate Germanic-shifted Balto-Finnic groups and Balto-Finnic groups influenced by their pronunciation.

- The intense Palaeo-Germanic and late Balto-Slavic / early Proto-Baltic superstrate on Balto-Finnic, which place all three dialects around the Baltic Sea since the Early Bronze Age.

- The easy replacement of a hypothetic Para-Balto-Finnic dialect by incoming Proto-Balto-Finnic-speaking peoples (say, with textile ceramics), without much linguistic impact.

In fact, the continuous contacts of the East Baltic with the Volga, and especially the close interaction with Akozino warrior-traders just before the Tarand-grave period, could be the actual origin of the recent (if any) Finnic-Mordvinic connections that need to be traced back to the LBA-IA (maybe here the number ‘ten’), since most of them can be related to a Pit-Comb Ware culture substrate and earlier contacts through the forest zone, which Samic (due to its early split and presence to the north of the Gulf of Finland during the BA) does not share. In fact, some of them can be traced back to Balto-Finnic first…

These are the most often mentioned, in order of descending relevance for a shared ancient community:

- Noun paradigms and the form and function of individual cases.

- The geminate *mm (foreign to Proto-Uralic before the development of Fennic under Germanic influence) and other non-Uralic consonant clusters.

- The change of numeral *luka ‘ten’ with (non-Uralic) *kümmen.

- The presence of loanwords of non-Uralic origin, related to farming and trees, potentially Palaeo-European in nature.

It’s not only a question of quantity. Are these shared Mordvinic – Balto-Finnic traits really more relevant than, say, those between Italo-Celtic, which are supposed to have formed a community for a very short period at the end of the 3rd millennium around the Alps? Are these traits even sufficient to propose a common early Mordvinic-Finnic group within West Uralic, rather than loose Mordvinic – Balto-Finnic contacts, i.e. contacts between East Baltic (Textile Ceramics) and Volga-Kama (Netted Ware)?

Based on the alternative (Kallio’s) view of continued contacts between Textile Ceramics groups, even without knowing anything about linguistics, you can guess that Parpola is spinning very thin when assuming that these changes suggest that Balto-Finnic may have expanded with Akozino warrior-traders, separating thus ca. 800 BC from Mordvinic…

Genetic findings now clearly help dismiss any meaningful population impact in the LBA-IA transition, although any linguist can obviously argue for linguistic change in spite of major genetic continuity. But then we are stuck in the pre-ancient DNA era, so what’s ancient DNA for.

Genetic continuity = language continuity?

In the end, it’s very difficult to say how much language continuity there is around Estonia since the arrival of Corded Ware peoples. Looking at Modern Estonians, they have been clearly influenced by recent contacts with Baltic- and Germanic-speaking peoples clustering to the south-west in the PCA. They seem to have also received contacts from north(-east)ern peoples, likely from Finland, evidenced by their shifts toward the modern Estonian cluster during and after the Middle Ages, with a slight increase in Siberian ancestry and N1c subclades associated with Lovozero Ware. How much language change did these contacts bring? Maybe an expansion of Gulf of Finland Finnic (Northern Estonian) over Inland Finnic (Southern Estonian) and Gulf of Riga Finnic (Livonian)? Difficult to know, exactly, but, in the traditional view of Balto-Finnic dialectal distribution among Uralicists like Kallio, possibly no change at all.

So, if the obvious changes in the Estonia_MA cluster relative to Estonia_IA cluster and Estonia_Modern relative to Estonia_MA do not represent radical language change…Why would Estonia_IA represent a change relative to Estonia_BA, when it is statistically basically the same? Or Estonia_BA relative to CWC_Baltic? Because of the infiltration of haplogroup N1c around the whole Baltic? Because of the occasional 1% “Siberian” ancestry in some non-locals of varied haplogroups across the whole Baltic area?

In spite of all this, the amount of special pleading we are seeing among openly Nordicist amateurs when discussing the Uralic homeland relative to the Indo-European question in genetics has become a matter of plain willful ignorance. Like the living corpses of the Anatolian homeland, the Armenian homeland, the OIT proponents, or the nativist Basque R1b association, the personal involvement in the revival of “R1a=Indo-European” and “N=Uralic” trends is just painful to watch.

[Next post in this line, if I manage to make time for it: “Genetic (dis)continuity in Central Europe“. Let’s see if early Balts and early Slavs, as well as Germanic peoples, show a cluster closer to Danubian EBA (viz. Maros), Hungary-Balkans BA, and Urnfield-related samples than their predecessors in their areas, i.e. away from East Corded Ware groups… If you want, you can enjoy for the moment the new PCAs I could get done and the tentative map of languages in the Early Bronze Age, that will probably give you the right idea about early Indo-European and Uralic population movements]

Related

- Uralic speakers formed clines of Corded Ware ancestry with WHG:ANE populations

- The cradle of Russians, an obvious Finno-Volgaic genetic hotspot

- Common Slavs from the Lower Danube, expanding with haplogroup E1b-V13?

- Aquitanians and Iberians of haplogroup R1b are exactly like Indo-Iranians and Balto-Slavs of haplogroup R1a

- Magyar tribes brought R1a-Z645, I2a-L621, and N1a-L392(xB197) lineages to the Carpathian Basin

- R1a-Z280 and R1a-Z93 shared by ancient Finno-Ugric populations; N1c-Tat expanded with Micro-Altaic

- The complex origin of Samoyedic-speaking populations

- Corded Ware—Uralic (IV): Hg R1a and N in Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic expansions

- Corded Ware—Uralic (III): “Siberian ancestry” and Ugric-Samoyedic expansions

- Corded Ware—Uralic (II): Finno-Permic and the expansion of N-L392/Siberian ancestry

- The traditional multilingualism of Siberian populations

- Corded Ware—Uralic (I): Differences and similarities with Yamna

- Haplogroup R1a and CWC ancestry predominate in Fennic, Ugric, and Samoyedic groups